Global crises often result in waves of reformations – will Covid-19 be the straw that breaks the back of apathy and lead to meaningful change?

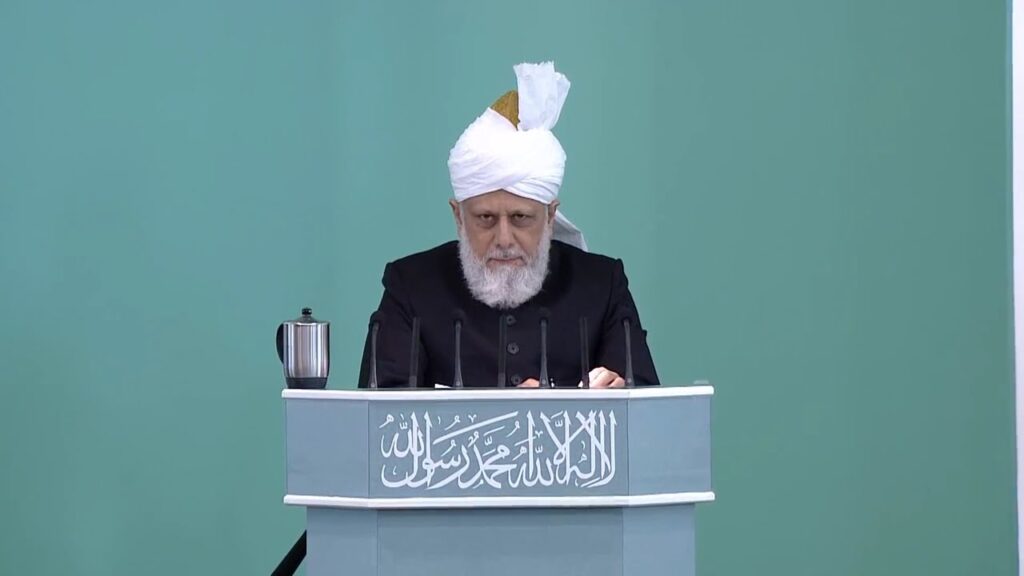

By Farhad Ahmad, staff member at the Press & Media Office of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community

I would hate to be a killjoy whilst you’re reminiscing about the good old days before Covid-19 but I must ask, were we not already standing on the brink of a financial crisis even before this lockdown? Covid-19 is undoubtedly having an unprecedented impact on the sinking of our economic ship, yet as late as 31 January 2020 – when it was not yet considered a major global threat – Kaushik Basu, former Chief Economist of the World Bank wrote, “The World Bank has just warned us that a fourth debt wave could dwarf the first three (1982, 1997, 2008).”

Whilst crises inspire dreams of the ‘golden past’, they are also said to rouse reforms. Where was the meaningful reform following the 2008 credit crunch? Unsustainable debt was the chief reason for the last financial crisis – yet a decade later in 2018, total global debt had risen to an historic peak of almost 230% of GDP.

Comparing the past decade with the decade that followed the Great Depression, former Governor of the Bank of England, Mervyn King, states: “The Great Depression was followed by political upheaval and, in economics, an intellectual revolution. This time around, we’ve got the political turmoil but no comparable questioning of the ideas underpinning economic policy.”

Is our apathy to consequential change so entrenched that we first need a crisis on the scale of the Great Depression before realising it may be time to scrutinise or question the very basis of our economic, political and philosophical system? If so, it appears the current situation offers us a unique chance to re-evaluate. As noted economist Nouriel Roubani writes, the shock to the global economy from the COVID-19 pandemic has been ‘faster and more severe’ than either the 2008 global financial crisis or the Great Depression. The financial crisis and Great Depression took three years to play out, this crisis is not yet three months old.

A new era and a new global order

In Forbes, Daniel Araya writes: “We are witnessing a restructuring of the global economic order that could lead to an entirely new civilization… Just as revolutionary movements have emerged in the past, so the combination of disease and economic contraction will provoke a new era and a new global order.”

If this analysis is correct, the potential for positive or negative change is huge. On the positives, a new awakening could lay the foundations for badly needed reform. Speculating about our future unknown, if the resolve exists to realise our potential as a civilisation, the political will and resolve to reform must go far beyond a few minor tweaks to the economic system. Indeed, we witnessed small and incremental changes after the 2008 crisis that were clearly not significant enough to tackle the fundamental forces that led up to the crisis.

The economic system does not exist in a vacuum. It draws life from systems so familiar to us, namely: capitalism, electoral democracy, human rights.

The West prides itself on freedom of thought and the ability to export ‘democracy-building’ projects, yet the real challenge rests in its willingness to grow, adapt and challenge the relevance and effectiveness of its own systems. As George Monbiot put it, to challenge ideologies such as capitalism today is equivalent to ‘secular blasphemy’.

You see, we must be willing to open our minds up to tough questions about our own strengths and weaknesses. Why not dare to venture into a genuine quest for alternatives? Increasingly, critics argue that we should not assume that today’s economic and political models are all perfect or inalienable. Mr Monbiot writes that “capitalism, by assuming material prosperity is the best way to achieve happiness… transformed our culture and society towards exploitation and violence.”

Are the pillars of democracy holding up?

Take electoral democracy. How is it holding up to the challenges of the 21st century? Economist-statistician Harold Hotelling published a paper in 1929 considered a pivotal resource in the study of electoral democracy.

In the words of Mr Basu, Hotelling’s paper “showed that political parties have a propensity to drift closer to each other, eventually creating a scenario in which there is little difference between the ‘left’ and the ‘right.’ This theory implied that over time all politicians will cater to the median voter.”

Rather than seeking the median voter, today’s political parties are pandering ever more to extremes traditionally located in the political hinterland. Democracy is most certainly under threat, but are there not fundamental problems that need to be addressed for a comprehensive solution? How will the systems which enable the rich to have enlarged influence upon politics and the media – cited as the backbone of democracy – be rearranged to allow greater trust in the institutions holding up democracy? These are questions we must envisage to be a part of wider reform narrative.

Are Modern views on human rights really set in stone?

Modern views on human rights are considered to be set in stone, yet they too must be viewed from a global perspective. Dr. Seth Kaplan, an academic at Johns Hopkins University makes an interesting observation in Foreign Policy that Westerners have played an “extraordinarily large role” in the academic work developing human rights.

As a result, human rights have become part of a modernist vision in which cultural normal from one part of the world have been converted into so-called ‘universal rights’, whilst “African, Asian, and other non-Western human rights institutions and laws are marginalized.”

For example, when it comes to human rights, certain countries have legally proscribed the right of women to cover their heads or parts of their faces. One can’t help but wonder if the same human rights ‘’warriors’’ would raise similar objections to women doctors wearing PPE face masks?

No wonder then, that a colonial tendency to impose one part of the world’s ideology onto others without consideration for local realities, in a connected world where countries are interdependent, is causing frustrations to build and so perhaps we already starting to see the tide turning against unrestricted globalisation. Apparently, ‘Slowbalisation’ is already coming to the fore, leading to deeper links within regional blocs.

Once we make it out of this crisis, sadly having lost many loved ones along the way, and we begin to navigate the emotional and financial toil it leaves behind, will there be enough resolve to finally question and ultimately reform some of the fundamental problems underpinning the systemic failures we were noticing before Covid-19? Will society be brave enough to bring about systemic changes in order to make the world a fairer and more just place? Will justice – as opposed to self-interest – be the new norm? I hope so. Let the apathy subside.